Drake was an enslaved potter in Edgefield, South Carolina who had been trained to make stoneware vessels.

By the mid-19th century, there were at least 12 potteries in west-central South Carolina. Drake worked in several, as one of 76 people known to have been enslaved in such commercial concerns. The largest, Pottersville Stoneware Manufactory, was owned by brothers Abner and Rev. John Landrum, who enslaved or hired Drake from his enslaver, revealing the intertwined connections in the Edgefield district. He was taught, or learned, to read and write, even though it was illegal under South Carolina law. Lewis Miles, his owner at the time Drake made this jug, allowed him to write on his utilitarian vessels, making this signed work extremely rare, and one that holds a world of untold narratives. Drake signed and often marked his vessels with poems, making them just a small number of exceptional examples known to be made by enslaved artisans. After emancipation, he continued to work as a potter, signing his work as David Drake.

While he made many jars, they were not considered as more than everyday storage containers in their time and have only gained value since the late 20th century for their association with a known Black maker. This jug fills a major gap in our Decorative Arts holdings as the first 19th-century object made and signed by a Black artist and craftsman to enter the collection.

How did we get to the winning bid?

We have a rigorous process for acquiring artworks that starts with a curator researching and vetting potential acquisitions within the framework of the Museum’s Collecting plan. An object like this David Drake jug has long been on our wish list as the Curatorial team seeks, with intention, to add artworks and objects by marginalized makers of color, women, and other underrepresented communities, such as LGBTQ+ artists. After this due diligence and deep research, the curator submits a proposal to me, and then presents it to our Acquisitions & Collections Committee, a subset of NMOA’s Board of Trustees, which meets twice annually. When a time-sensitive opportunity arises, such as an auction, we seek approval to bid from the Committee. Thanks to the intrepid members of the Committee and their unanimous support, Amy and Catherine were able to stay in the race, along with a number of anonymous bidders, including at least one other museum. The jug will debut in our 18th and 19th century American galleries next March when we unveil a major reinstallation that presents the collections through the lens of slavery and Black history.

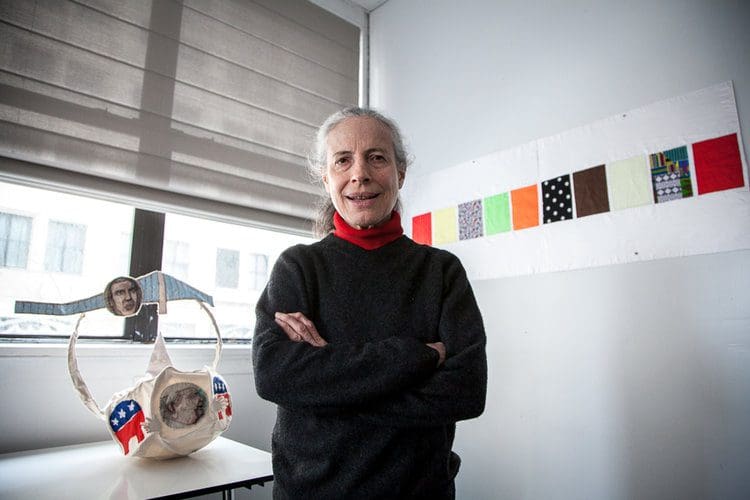

Collections are mere objects without the people who bring them to life for our audiences. This week’s letter is in honor of Doris Froelich, one of our treasured and dedicated former docents who passed away recently.

In gratitude,

Linda C. Harrison

Director and CEO

The Newark Museum of Art